Capitec's Results: The Power of Serving the Underserved Pt 1

Capitec became South Africa's most valuable bank by serving lower-income customers ignored by traditional banks, who were paying up to 2,230% annual interest to loan sharks. While larger banks like ABSA failed in microlending due to poor execution and viewed the segment as too small to prioritize, Capitec's focused approach and low-cost model drove 400% income growth over the past decade. This demonstrates how smaller players can win by intensely focusing on underserved niches that established competitors overlook.

9/8/20254 min read

Capitec's Results: The Power of Serving the Underserved Pt 1

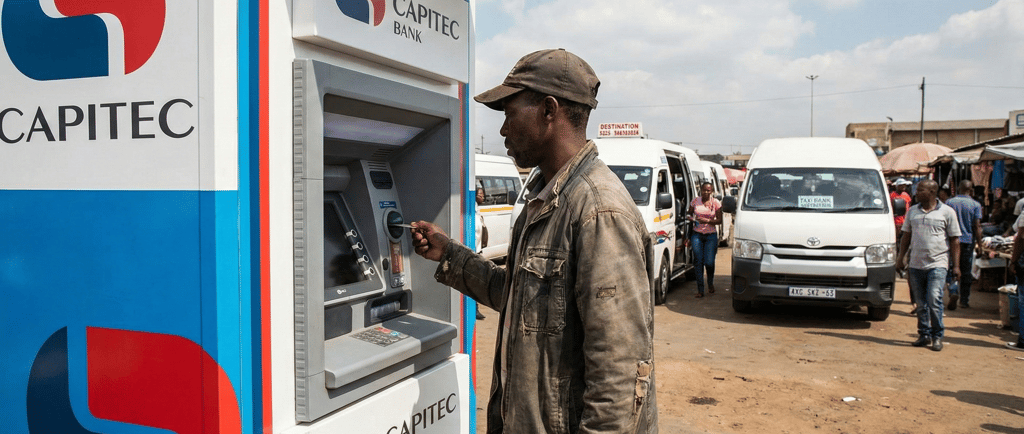

Twenty years ago, Capitec was a small bank serving the lower-income category of South Africa, so much so that it placed its branches near taxi ranks to cater for its customer base.

Twenty years later, Capitec became the most valuable bank in South Africa, growing over 30,000% over that time.

How did focusing on a low-income customer base generate such extraordinary returns?

Let's unpack.

Capitec's Financial Results

Capitec had another strong start to the year, with income up 27% and earnings (profit) up 26% compared to the previous half-year.

Part of the growth was due to the acquisition of Avafin, a fintech company operating in North America and Europe. However, even adjusted for that, income was still up 23% and earnings 25%.

This is really impressive, considering that most banks in South Africa grew between 5% and 10%.

This higher-than-market growth has lasted for a while. In the last 10 years, Capitec has grown its income by close to 400% while Nedbank, for example, has increased its income by about 60%.

This is not to say that Nedbank is underperforming, but more to illustrate that the strategic approach that Capitec took early on is really hard to match and creates long-term upside.

Before digging further, we need to lay the foundation to understand why Capitec has sustained so much growth over the last twenty years.

It all can be underpinned by one principle: serving the underserved.

Capitec's History and Foundation for Success

The best customers are the ones who have a big problem that is being ignored by the market.

In the early 2000s, when Capitec started, lower-income South Africans who needed affordable unsecured microloans were the ignored segment.

Traditional banks had viewed this segment as too risky and unprofitable, forcing people to borrow from loan sharks instead.

Capitec's 2003 annual report illustrates this well. At that time, the industry norm was that people who needed small unsecured loans typically had to pay interest of 30% per month, or a staggering 2,230% annually.

Note that the lending rate banks were offering customers was around 15%, so this segment of the market was being massively overcharged—paying over 2,000% more.

Capitec was "cheap" at 22% per month (which was still about 984% per year), but even they recognised that these amounts were excessive and that the way to be successful was to "reduce prices, help the customer and beat the competition."

The issues with the high cost of credit, as well as other unfair practices, also prompted the development of the National Credit Act, which ended up putting some limitations on interest rates that could be charged.

At the time, it was clear that there was a large segment of the population that needed credit but was unable to access it.

So why didn't other banks tap into this segment that seemed positioned for growth?

Why Other Banks Didn't Follow Capitec

It wouldn't be accurate to say that banks completely overlooked this segment.

The best example is ABSA. In April 2000, ABSA acquired a majority stake in UniFer, one of the leading third-party microlenders, paying over R1 billion in what was its first significant acquisition in almost a decade.

UniFer was much bigger than Capitec. It actually took Capitec five years to reach the size of the loan book that UniFer had in 2000.

Unfortunately, the UniFer acquisition ended up being an absolute disaster for ABSA, with UniFer collapsing just two years after it was bought.

UniFer had a lot of hidden issues that included management conflicts of interest, reckless loan growth, unauthorised lending, executive kickbacks, and weak internal credit controls.

This ultimately resulted in ABSA taking well over a billion rand in losses.

Perhaps this disastrous encounter made other banks more risk-averse to entering the space.

What also played a part was that the traditional banks were doing well enough. According to ABSA's 2003 annual report, in 2002/2003, the big four banks controlled 75% of the retail lending market.

To target the microlending space would have required increased focus and more aggressive cost discipline to allow for the low-cost lending approach.

In addition, the unsecured microlending business was still small. For ABSA, microlending was less than 3% of its loan book, even after acquiring one of the largest players.

With all these factors, the natural approach for any bank would have been to focus on what it already controlled and was making money from. This happens more often than we think.

Join 5,000+ readers of Money & Moves who get concise, insightful takes on business, strategy, and finance in Africa.

Why Large Companies Lose To Smaller Players

Large, established companies frequently get beaten out by new entrants that focus intensely on niche segments, which the larger company considers secondary.

An example is Coca-Cola and the energy drink segment. While Coca-Cola remains the world's dominant soft drink company, it has struggled to win in the energy drink segment.

Red Bull entered and successfully built a powerful brand by pioneering and focusing on the category, and now controls roughly 36% of the US energy-drink market.

Perhaps even more remarkable is that this repeated itself with Monster Energy, entering the same segment and also surpassing the other brands that Coca-Cola had.

This time, however, Coca-Cola, recognising the success of Monster, decided to partner rather than compete and invested about US$2.15 billion in 2014 for a 16.7% stake, transferring its other energy brands to Monster.

This might have been an acknowledgement that highly focused and determined competitors are difficult for larger, well-established companies to beat. It serves as a key lesson for any business when competing against a bigger player.

This was the same with Capitec. They were all in on this underserved segment and could build their business and strategy entirely around it, including adopting a lower-cost digital-first structure.

They summed it up well in one of their early annual reports:

"We remain on track to build something unique: a low-cost, full-service mass market bank."

What happened next was magical and will help us analyse their current financial results in more detail and draw lessons that can be applied to any business, especially those in Africa.

Since there is so much to unpack, we will need to pause for now.

Part 2 will be coming next week.

Let me know if you have any comments or questions which we could then cover in Part 2 as well.